RALEIGH – During graduate school in Denmark, Stephanie Michelsen was one of a select few awarded a fellowship that brought students to San Francisco for a five-month stint working at biotech and engineering startups. There she was introduced to alternative proteins by researching how fungi can be made into a meatless dog food. Michelsen also got a taste of this burgeoning segment of biotech as a consumer when she tried an Impossible Burger. The overall experience was her first time seeing the intersection of hardcore science and food, she recalled.

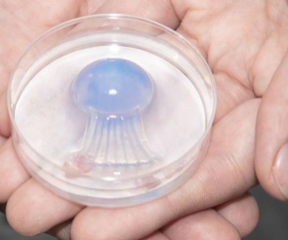

Jellatech image

Michelsen’s spell in the Bay Area reinforced her ambition to combine biotechnology with entrepreneurship. Upon returning to Denmark to complete her degree in engineering in biotechnology, she pondered how to accomplish her goal. A growing number of startups are researching proteins that can be made as alternatives to meat proteins. But Michelsen found none addressing collagen, a protein key to making many foods, wine and beer, cosmetics, and even some pharmaceuticals.

— Jellatech photos

“This protein ties into so many different products, so many different sectors, and we don’t even think about it,” she said. “At the same time, there is no animal-free version. I thought we could solve it with biotech.”

And so Michelsen founded Jellatech, a Raleigh-based startup that is developing a collagen-production process. But rather than try to engineer a collagen alternative, Jellatech is producing the same collagen that comes from animals—without using any animals. The collagen is produced by fibroblasts, the most common type of cell in animal connective tissue, said Michelsen, the company’s CEO. Jellatech cultures these collagen-secreting cells in bioreactors that mimic the animal environment.

Jellatech is currently researching collagen production from four types of fibroblasts: human, bovine, porcine, and marine. The company does not engineer those fibroblasts in any way, Michelsen said. In the bioreactor, the cells start producing collagen quickly. How much is produced depends on the number of fibroblasts used and how long those cells are cultured. It’s a continuous process and the longer it goes on, the more collagen that’s produced. Once collagen is produced, it can be further refined into gelatin.

“In our process, you don’t need to wait two to three years for a cow or pig to grow big enough,” Michelsen said. “Why grow an entire animal when you can grow only the part that you need?”

Bypassing the slaughterhouse

Animals aren’t grown specifically for collagen, of course. The collagen currently used in various industrial applications comes from animal agriculture, where it is a byproduct. Isolating the collagen is a multi-step process that includes procuring the animals from a slaughterhouse, separating the collagen by boiling bones and animal hides, and purifying the collagen. Globally, this collagen market was valued at $3.6 billion last year, according to a recent report from research firm Global Market Insights. The gelatin segment of the collagen market alone was worth more than $1.57 billion in 2020. Food and beverage applications, where collagen is used as a gelling agent, and health care, where collagen can be found in biotechnology products and wound dressings, are driving the market’s growth, the report said.

The fibroblasts Jellatech selects determine its application. Human collagen isn’t for consumable products but is used in biomedical applications and cosmetics, Michelsen said. Collagen from marine sources is used in a wide range of sectors. Bovine and porcine collagen are used in food products. Michelsen said it’s too soon to compare the cost of Jellatech’s process to the way collagen is currently produced. The startup is in the R&D phase and still needs to optimize its production and bring it to scale. But she added that Jellatech’s approach can ensure consistency in the supply and quality of collagen.

Michelsen, who grew up in Denmark and Sweden and now holds a green card, moved to the Triangle sight unseen. Her primary familiarity with the U.S. was the Bay Area; the only East Coast city she had ever visited was Boston. As Michelsen contemplated where to base her new company, she decided on the U.S. rather than Europe. The Bay Area is a great place for startups generally and biotech specifically, she said, but it’s also very crowded and expensive. An East Coast location would put the company in a time zone closer to Europe and potential partners there. Also, Kylie Hesp, Jellatech’s co-founder and head of science, is based in the Netherlands.

Michelson did some research on the Research Triangle, consulting with local startup founders. She concluded the Triangle offered the opportunity to grow in an affordable biotech hub that can also provide her young company with access to talent from the region’s research universities.

Raised $2 million pre-seed round of investment

In April, Jellatech announced its first financing, a $2 million pre-seed round. Investors include Iron Grey, YellowDog, Seven Hound Ventures, Capital V, Sentient Investments, Bluestein Ventures, Sustainable Food Ventures, and Big Idea Ventures. The capital enables the company to expand; it currently operates in a small Raleigh office and Michelsen is negotiating for larger space in the Triangle, which she plans to move the company into in coming months.

Jellatech is already working with several undisclosed partners in various sectors. Michelsen said that the company had to be selective about which companies to work with because the startup’s production process is still limited in how much collagen it can produce. But she said that those partners are receiving small quantities of collagen and providing Jellatech with feedback. The long-term goal is to make Jellatech into an ingredients supplier to companies that will use the animal-free collagen to make their own products. The startup will begin with companies in higher-end collagen applications, such as biomedical products and cosmetics. After establishing a presence in those sectors, the startup would move on to applications at lower price points, such as food and beverages.

In the nearer term, Michelsen said Jellatech needs to speak with regulatory authorities to better understand the requirements for producing collagen for various applications. The company will also continue to refine its collagen-production process.

“Scaling the company, scaling the technology,” Michelsen said. “Those are the major next steps for us.”

(C) N.C. Biotech Center