Editor’s note: Contributing to this report were Maryann P. Feldman, S.K. Heninger Distinguished Professor of Public Policy and Professor of Finance, Faculty Director of CREATE, as well as Frederick Guy, Department of Management, Birkbeck, University of London; Simona Iammarino, Professor of Economic Geography, London School of Economics; and Carolin Ioramashvili, Ph.D. candidate in Economic Geography, London School of Economics.

CHAPEL HILL – There are signs of a growing bipartisan agreement in Washington that Big Tech — Facebook, Google parent company Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft and a handful of other technology giants — needs to be more tightly regulated. And it’s not just talk.

Several bills aimed at Big Tech have been introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives. In June, the Ending Platform Monopolies Act (HR 3825) was approved by the Judiciary Committee and sent to the floor for consideration by the full chamber.

Successful efforts to rein in Big Tech could boost efforts around the country to develop local tech clusters. That’s because the concentration of the largest technology companies in a small number of regions — especially Silicon Valley — has created an economic vortex that tech startups from other regions are often pulled into.

The Startup Lifecycle

Research by Maryann Feldman, director of CREATE at the Kenan Institute – in partnership with Simona Iammarino and Carolin Ioramashvili from the London School of Economics and Political Science and Frederick Guy from the University of London – examines how acquisitions of small technology firms by large technology companies exacerbate economic inequality between regions.

Related headlines

Good news for Epic? Senate bill targets Apple, Google app store dominance

‘Big Tech’ antitrust legislation will hit small business too, think tank warns

The researchers described some of the technology industry dynamics that give Big Tech so much influence and have concentrated economic power in just a handful of U.S. regions, even as the forces of innovation and entrepreneurship generate a steady stream of startups.

For tech startups, venture capital financing is often required to achieve scale. This inevitably leads to one of two potential paths for a profitable exit. The less common strategy is growing the company to the point where it can issue stock in an initial public offering (IPO); however, IPOs are relatively rare.

The more common strategy is for startups to be acquired by larger technology companies, making acquisition a goal for many. And therein lies the “winner-take-all” dynamic that gives a few regions, such as Silicon Valley, the lion’s share of technology entrepreneurship success and its accompanying wealth.

For their study, Feldman and her colleagues defined Big Tech as the seven largest U.S. technology firms by market capitalization: Amazon, Alphabet (the parent of Google), Apple, Microsoft, Facebook, Oracle and Adobe. Each of them began as a startup and all, except Oracle, received venture capital funding, grew quickly, went public and became powerful, monopolistic technology platforms.

Importantly, all of them have grown in part by acquiring smaller companies, allowing them to incorporate new technology, hire high-value talent and, sometimes, stifle competition.

To better understand startup acquisition dynamics, Feldman and her colleagues examined the acquisitions made by Big Tech firms and their subsidiaries — 674 U.S. acquisitions out of a total of 940 worldwide. Alphabet and Microsoft have been the most prolific acquirers, together accounting for half of all the acquisitions in the group.

Moving Away

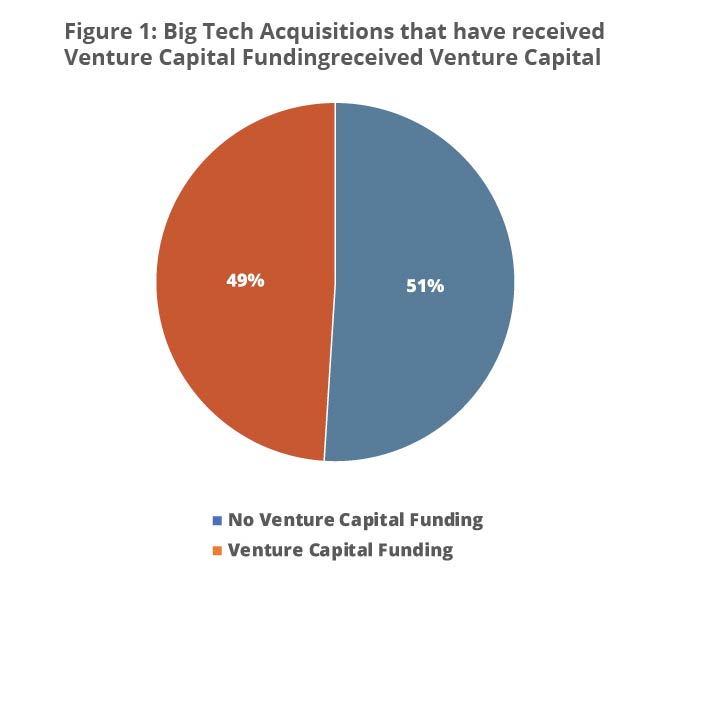

Feldman and her colleagues did a deeper analysis of Big Tech acquisitions, looking at the 603 U.S. startups acquired from 2001-2020. They discovered that nearly half (49%) had received venture capital funding. Angel investors, wealth and investment management firms, banks, two universities and a public-private investment fund were also sources of equity backing.

When founders take outside investment, they increase the pressure on themselves to produce an exit event that will create a positive investment return for those equity investors.

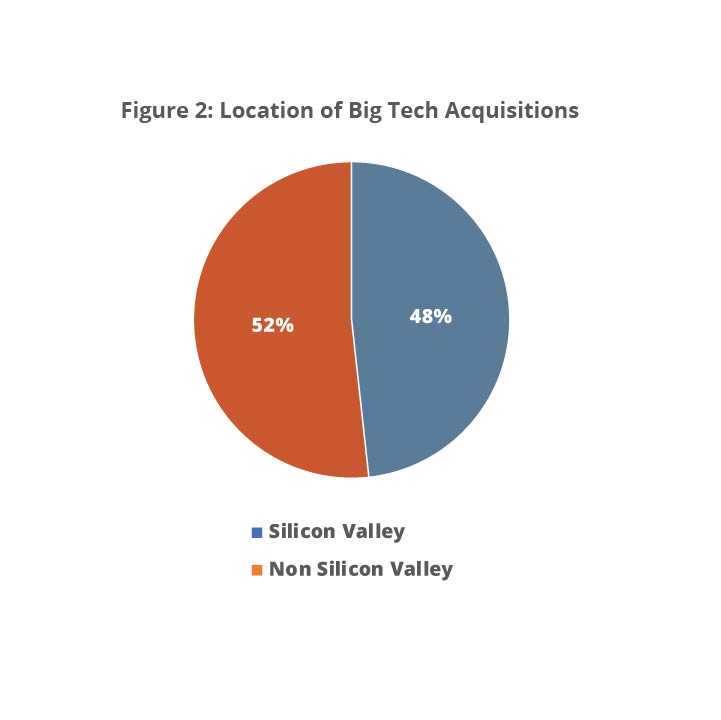

Of those firms, 291 — nearly half — were located in Silicon Valley, which Feldman and her colleagues defined as the combined San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara and San Francisco-Oakland-Berkeley metropolitan statistical areas.

While it is difficult to trace the origins of so many firms, the researchers estimate that a quarter of the Silicon Valley acquisitions were launched elsewhere and subsequently moved there. There are a multitude of factors that make moving to Silicon Valley attractive for founders.

Feldman and her co-authors compared the Big Tech acquisitions to four other sets of firms seeking financing: 6,213 tech firms that received Small Business Administration (SBA) 7(a) loan guarantees, using these loans as an indication of the company’s credit worthiness; 3,005 tech firms that were acquired by a purchaser other than the seven Big Tech companies; 196 tech firms that went public on the NASDAQ; and 1,030 tech firms sold by VC firms that also sold companies to Big Tech.

Silicon Valley has the highest count of firms in all of the above categories except for the SBA loan recipients. The geographic distribution of this broader measure of tech firms was more diverse and included university towns. Yet these places drop out when considering exits. Regression analysis suggests that being located in Silicon Valley increases the probability of being acquired by Big Tech by 17 percentage points.

A firm being backed by a venture capitalist makes it more likely that a firm will be acquired by a non-Big Tech firm. Whether the VC is in Silicon Valley doesn’t have any impact on whether Big Tech will be the acquirer. However, if the VC was an early backer of one of the Big Tech companies, there was a positive and statistically significantly effect on the likelihood of a Big Tech acquisition.

For IPOs, being in Silicon Valley has a strong positive effect on the probability of achieving a public offering. However, having a venture capitalist backer has a negative effect on IPO probability, and a Silicon Valley-based VC investor is significantly negative. Whether a VC was an early backer of Big Tech doesn’t have a significant impact on IPO likelihood.

Competitive Implications

The gravitational pull that Big Tech and their surrounding regions exert on startups has important implications for competitiveness in the technology industry as well as for the efforts of local economic developers. An earlier paper argued that the divide between wealthy and poor places is deepened by monopoly power, and in particular by the power of large digital platform companies.[i] The power of these companies amplifies the centripetal pull of agglomeration economies for two reasons. First, the productivity of labor is augmented by monopoly rents, some portion of which is shared in the form of high remuneration for a stratum of skilled workers. The second is the market for acquisitions, with the result that some of the platform’s rents will be shared among the owners and key employees of the startup within major tech hubs. However, the places were the startups were incubated are left behind.

Other researchers have found that startups seeking to be acquired are biased toward inventions that improve an industry leader’s technology1 in order to make themselves more attractive acquisition targets, rather than developing an alternative. This reduces innovation and competition.

Further, acquisitions create a winner-take-all, first-to-market dynamic. When a product is acquired by a larger tech company, other competing projects are likely to struggle to win customers and capital because of the perception that the acquired company “won” the race to be acquired.2

Furthermore, prior research3 has estimated that 5.3% to 7.4% of U.S. acquisitions between 1989 and 2010 were purchased to kill a competing product. Many acquired products are discontinued after acquisition, suggesting the acquisition was motivated by a desire for intellectual property rights, talent or other intangible assets.

The implications for growth and competitiveness in areas outside a handful of technology clusters is, likewise, dire. Technical talent and entrepreneurial drive — as well as universities and other supporting institutions — are distributed in many places. For local economic developers, the prospect of developing a technology creates the promise of, perhaps, also developing the kind of wealth and prosperity seen in places such as San Francisco and Boston.

But those economic development aspirations can only come to pass if startups that launch in a community and stay in that community. Ideally, companies should be able to grow in the places that initially invested in them. In those circumstances, company founders and employees — and their wealth — are more likely to stay local. But if moving to Silicon Valley provides a more promising path to securing needed investment, many founders will pursue it. And when those founders leave, the wealth their venture might generate is unlikely to return.

Stopping the Giant Sucking Sound

For policymakers, the allure that tech clusters create for startup firms is challenging. On the one hand, if all of the success those tech companies enjoy is due to the concentration of particular resources — talent, financing, and so forth — then breaking up those clusters could kill the goose, as it were, that laid the golden egg.

However, if Big Tech’s sway over innovation and start-up activity is in part through the power of their monopolistic platforms (ex. the Apple and Android app stores), then traditional antitrust prescriptions — regulating and/or breaking up large tech companies — are likely to not only make the technology industry more competitive, but also strengthen local economies and boost entrepreneurial ecosystems across the country.

This post was published originally at this site. It is reprinted with permission.

1 Argentesi, Elena, Paolo Buccirossi, Emilio Calvano, Tomaso Duso, Alessia Marrazzo, and Salvatore Nava. 2019. “Merger Policy in Digital Markets: An Ex-Post Assessment.” DIW Discussion Papers; Gautier, Axel, and Joe Lamesch. 2020. “Mergers in the Digital Economy.” Information Economics and Policy, September, 100890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoecopol.2020.100890.

2 Kamepalli, Sai Krishna, Raghuram Rajan, and Luigi Zingales. 2020. “Kill Zone.” National Bureau of Economic Research.

3 Cunningham, Colleen, Florian Ederer, and Song Ma. 2021. “Killer Acquisitions.” Journal of Political Economy, February. https://doi.org/10.1086/712506.

4 Gautier and Lamesch. “Mergers.”